ARCHIVE

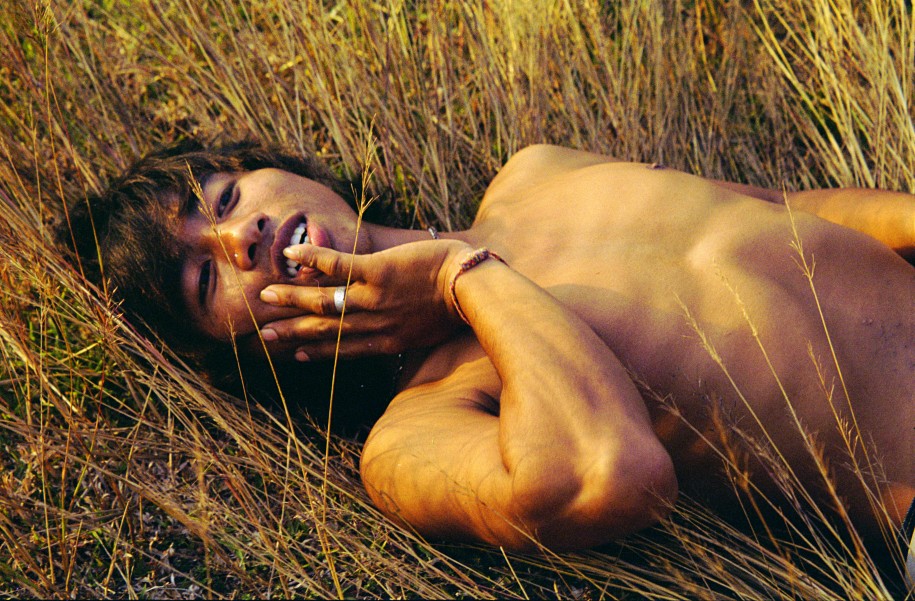

APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL

words by Carson Chan

Courtesy of Haus der Kunst, Munich; FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), Liverpool and Animate Projects, London

The international reception of Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films has been polar: where some have found a new obsession, others pooh-pooh them as intellectual claptrap. Since Mysterious Object at Noon (2000), his first feature-length international release, each successive film has been concurrently lauded by cineastes worldwide and snubbed by audiences in his home country. In 2008, a year after an official at the Thai Ministry of Culture told Time Magazine that “nobody goes to see films by Apichatpong [because] Thai people want to see comedy, we like a laugh,” Apichatpong received both the Fine Art Prize from the 55th Carnegie International in Pittsburgh and Knighthood in the Order of Arts and Letters from the French Ministry of Culture and Communications. Museums in North America and Europe have likewise celebrated the filmmaker with screenings of his short films and exhibitions of his video installations. Exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo (2007), L’Espace Culturel Louis Vuitton in Paris(2008), and the Haus der Kunst in Munich (2009) exist as collateral support for the young filmmaker as he battles censorship, mockery and rejection back home. Bangkok Post film critic Kong Rithdee recounted that when Tropical Malady (2004) won a Jury Prize at Cannes, a famous Thai news anchor, lampooning the perceived high-mindedness of the film, said, “I have to climb a ladder to see his film.” The collected press clippings from Apichatpong’s exhibition in Munich, filled with unabashed praise and philosophicalanalyses, measure about an inch thick, and his film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) became the first Thai film to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Yet in spite of this critical embrace and prestige, it may be a few years still before attentions in Thailand shift from his newfound celebrity to his life’s work.

Courtesy of Haus der Kunst, Munich; FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), Liverpool and Animate Projects, London

Much has also been made of the enigmatic nature of his cinema, yet few voices have ventured forward from this observation. A new volume devoted to Apichatpong’s work, edited by James Quandt, film programmer at the Cinematheque Ontario in Toronto, offers a kind of I Ching to the filmmaker’s elusive contrivances. Quandt’s book—the first English language anthology dedicated to the director and his work—compiles the writing of film critics and filmmakers, including interviews and texts by Apichatpong himself. Many of the book’s contributors make no secret of their devotion to the filmmaker’s work, their sympathies for his plighted relationship with Thai censors, and their obsessive, meticulous knowledge of their subject and his work. The book’s annotated filmography, with detailed plot analyses of each feature film, and a keenly probing interview with Apichatpong add much to the general understanding and scholarship of Apichatpong’s practice, but depending on the reader’s preexisting affinity for the oeuvre, most of the book will read either as self-affirming or simply alienating. “Everyone,” Tony Rayns states in his essay, “knows by now that Apichatpong is the son of two doctors and spent his boyhood living in the hospital in Khon Kaen and observing his parents.” The letters between Mark Cousins and Tilda Swinton that open the book are so replete with intimate musings and hammed adulation over Apichatpong that our admiration for the writers’ emotions turns critical. Cousins tell us that he’s writing about Apichatpong in his long johns as the clouds race across the dawn sky of Edinburgh; Swinton’s letter (literally) breaks into stanzas of poetry before she continues on about showing Apichatpong’s films to her children. “I wish we could show my children these films, although I know we won’t for some years. I feel they would settle them, give them a divining rod for the future, when the light might trick them into thinking editing is the answer to a sense of real power in life.”

Helpfully, Quandt’s own contributions lay plain and demystify Apichatpong’s films by thoughtfully scrutinizing each shot for its motives, rather than playing up the mysterious, exotic and opaque characterizations given to the films by the commercial press. Concepts and motifs (like the jungle, rural Thai life, folklore, binary structures, Buddhism, doctors, etc.) articulated throughout Apichatpong’s films are identified, cross-referenced and theorized at length in relation to the director’s biography—much of which is warmly recounted in a translation of an essay by Apichatpong that first appeared in Sat Vikal (2007), a book about sexuality in Thai film and art. The reappearance of doctors in several of the films gives Quandt the opportunity to conjure rich relations between Apichatpong’s parents (who we now know are doctors), the divide between traditional and modern Thai culture, and the desire for cures.

Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok; Illuminations Films for New Crowned Hope, London

Readers less obsessive than Quandt will find some of his own remarks wanting in focus. In his essay about Blissfully Yours (2002), we’re told that five characters have names starting with N when translated into roman letters, and that the teenager at the hospital being treated for monoxide poisoning has a tattoo that says “Pandora.” Rayns rightly noted that “Apichatpong doesn’t fetishize his memories,” so why should we? Where the book seemsat odds with Apichatpong’s films is the amount of energy spent poring over every held moment, bit of dialog, and cinematic device employed, while acknowledging the real-time, unadorned simplicity of expression in his films. Quandt’s book is impressive in its breadth of personal insight (anecdotes about the filmmaker’s favorite films, etc.) and clear contextualization of the works within cinema history, but one wonders if the perfervid and plentiful analyses will, at least for those who watch films for pleasure, distract from the uncomplicated poetry of the films themselves. Apichatpong is often noted for his sustained shots that never leave actions abbreviated and for his digressing plot lines that progress without a definitive end. In the interview included on the DVD of Syndromes and a Century (2006), Apichatpong explained that he is “interested in plot, but not interested in developing it.” Sustaining a shot for the entirety of the action it portrays, as if the action were documented rather than filmed, exposes the latent drama in our most banal activities. If Roong and Min’s car ride into the countryside midway through Blissfully lacks conversation, it is to give voice to the confined space of the car, the racing landscape out the windows, and the sensation of movement as the car turns corners. In Syndromes, we watch for several minutes as a dentist’s assistant prepares the materials for a teeth cleaning; the dentist and the patient, a monk,wait as we do, as the assistant unhurriedly performs her routine. One’s mind wanders when sitting for a dentist, both to wile away the tedium of the visit, and to distract from the occasional pain. Enacting banality as a way to connect the filmic lifeworld with the viewer’s reality, Apichatpong complicates the distinctions between the world onscreen and off. To sit in the car for what feels like the entirety of Roong and Min’s drive changes the film from something we watch into something we experience. The long, languorous shots of trees bending to the wind that appear in several of the films seem to motion us towards the innumerable potentials possible within each form, and the incalculable complexity of even the most commonplace of settings. The flutter of each leaf, the arch of each branch, and the collective eddying of the trees mesmerize us, if we allow them.

Apichatpong was born in 1970 in Bangkok, but grew up in northeast Thailand, Khon Kaen, where he studied architecture at the local university. He began making short films and videos in 1994, the same year he became a member of the Association of theSiamese Architects. Around the same time, he enrolled for a Masters in Fine Arts in Filmmaking at the School of the Arts Institute of Chicago, and even before graduating in 1997, he had helped found an independent production network for young Thai filmmakers called 9/6 Cinema Factory. He launched his own film company Kick the Machine in 1999, and completed his first feature, Mysterious Objects at Noon, a year later.

Coming of age in Khon Kaen in the 1970s and 1980s, as metropolitan centers in Thailand, namely Bangkok, modernized with fervor, Apichatpong must have felt the growing differences between city and country being marked along ideological and, to a degree, racial lines. From a Northerner’s perspective, Bangkok was commerce-driven, detached

from its past and Americanized, while the “up country” embodied authentic Thainess, still operating within a worldview where the routines of daily living freely channeled myth and tradition, and where familial memories remained alive in the continuation of generations. This is important to keep in mind, particularly for Benedict Anderson’s essay, which contextualizes the reception of Apichatpong’s films within the Thai cultural sphere.

Anderson argues that this milieu is metropolitan and not representative of Thai audiences in general. For Anderson, the weak response from the Thai public is not due to the factthat the films are not Thai enough, nor because they seem to be like Western experimental film, which is unfamiliar to local audiences in general, but rather because major film centers in the country, like Bangkok, are themselves too Westernized in their commercial film culture to see how enrooted these films are in Thai sensibilities. The aforementioned official at the Thai Ministry of Culture Ladda Tangsupachai’s damning charge that Thai filmgoers are too “uneducated” to justify censorship was challenged by film critic Alongkot Maiduang’s (a.k.a. Kanlaphraphruek) mockumentary called Room Kat Sat Pralaat, or Ganging Up on ‘Sat Pralaat’ (2004). In it, “up country” villagers were shown Apichatpong’s Sat Pralaat (Tropical Malady, 2004), to their full understanding and enjoyment.

Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok; Illuminations Films Past Lives, London

Furthermore, the villagers (two men and one woman) interviewed found no objection to the homosexual romance developing between the protagonists, and offered that it was, in fact, “quite ordinary” where they came from. Anderson also recounts a conversation about Tropical Malady he had with an Indonesian friend who grew up in the jungle. “This is the most wonderful movie I have seen. I can’t believe that anyone making a film today could get inside the world in which I grew up, and present it with such perfection. I’ve never seen anything like it.” The idea of seeing something that one has never seen before is perhaps further from the self-perception of, and therefore more challenging to, Thai city dwellers than the country’s rural majority. Superstition, animism and folklore have an intrinsic and ineffable logic outside of Thai cities, where natural, unmediated forces are incorporated into the space of social interactions. The jungle, far from being a place of mystery as some of Apichatpong’s observers maintain, is a place where people live out their lives in social structures more integral, ancestral, though no less contemporary, than their metropolitan counterparts. Contentiously, Anderson understands the detachment Bangkokians feel towards Apichatpong’s films through Sujit Wongthes’s book, Jek Pon Lao (1987): In operating within the world view sensitive to “up country” folk, Apichatpong’s films alienate the city dwelling bourgeoisie, who since the nineteenth century, have been made up of Thais with Chinese ancestry, the luk jin, or more colloquially, the jek of Wongthes’ book, who continue to control the social and economic bearings of the Thai city set.

When cinema was introduced to Thailand at the end of the nineteenth century, according to Scot Barmé in his research on Thai cinema history, it was in the playhouses of the elite and mounted by foreigners. After the first film screening in the summer of 1897 at a playhouse owned by Prince Alangkan, where more than six hundred patrons showed up to watch a film of a boxing match and a film of an underwater diver, the royal family took notice and requested private viewings. These first films were referred to in the Thai press as nang farang, or foreign shadow theater, to separate them from the traditional shadow theaters popular with rural Thais. Also in 1897, King Chulalongkorn was introduced to and recorded on film during his visits to Berne and, two months later, Stockholm—news that excited Thais back home. Japanese investors took notice of the growing Thai interest in film, and from 1904, when a tent capable of seating one thousand people was erected in central Bangkok by Japanese film investor Tomoyori Watanabe, to 1910, when the King formed the association The Royal Japanese Cinematograph made up of Japanese cinema owners, the ur-signifier of cinema in Thailand was established in its representation of all things elite (royal), modern and foreign.

Courtesy of Kick the Machine Films, Bangkok; Illuminations Films Past Lives, London

Visuality, it seems, has been particularly instrumental as a device for Thai power structures, particularly the monarchy, to maintain the impression of a panopticon-like control over the people. Prince Sanphasat Suphakit, King Chulalongkorn’s younger brother, was one of the earliest Thai filmmakers. In 1900, he had acquired filmmaking equipment from Europe, and began immediately to make short documentaries like the one he showed in 1903 at the Oriental Hotel depicting the thirtieth anniversary of his brother’s reign. In 1922, Prince Kamphaengphet and Prince Purachat founded the Royal Siamese Rail Film Unit and used it to document the regions of the country. Collecting and depicting the various dress, customs and environments served not only to record both the diversity and unity of the Thai people, but to confirm the dominance of the monarchy through their proven ability to capture the lifeworld of its people. Thailand’s current ruler, the bespectacled King Bhumibol, whose eyesight was partially lost due to a car accident, is today often depicted in posters and announcement boards around Thailand with a pair of binoculars and a camera by his side—technical aids to remind Thai citizens of his symbolic ability to maintain an overview of his land and its people.

Puzzlingly, a year after Thailand’s Ministry of Culture bestowed Apichatpong with the Silpathorn Award, the country’s most prestigious visual arts award, Syndromes (2006) was banned from domestic release after the filmmaker refused to take out four scenes that the Ministry deemed unsuitable for Thai viewers. These scenes included depictions of (heterosexual, clothed) doctors kissing, other doctors drinking in a hospital, a young Buddhist monk strumming on a guitar, and two other monks playing with a remote controlled flying saucer. It appears that the Ministry of Culture, which Anderson suggests harbors a conception of Thai culture extant only in Bangkok, saw the potential damage these scenes could foster within a constructed, conservative worldview where doctors are ethical, law-abiding paragons of decency, and monks are symbols of the premodern, Buddhist bedrock from which the Thai derive their moral and emotional center. Challenges to this balance—as Hollywood films routinely do in Thailand without censorship—are dangerously effectual only when posed by a Thai.