ARCHIVE

“PAINTER PAINTER”

interview by Cristina Travaglini

Courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

CRISTINA TRAVAGLINI You are set to curate a group show, tellingly entitled “Painter Painter” and featuring new works by 15 artists, that will be open at Walker Art Center next February. The exhibition focuses on the centrality of the studio as a site of individual creativity. In a time when art practices are facing an increasing dispersion, what remains unique in the dynamics of daily studio practice?

ERIC CROSBY This issue of dispersion foregrounds, for me, how interested we’ve all become with painting’s immaterial life—its reproduction and circulation in the world. Right now, as we look toward the opening, our attention is really focused elsewhere: specifically on how a collection of very real objects will occupy a space. That said, as we began to develop “Painter Painter,” Bart and I initiated our conversation by questioning the resolute materiality of painting, which continues to attract artists to the medium today. I would say my current interest is really focused on painting as an object that can narrate a deeply individuated way of thinking with materials. An aesthetic context of dispersion creates a lot of noise in this train of thought, but I welcome it.

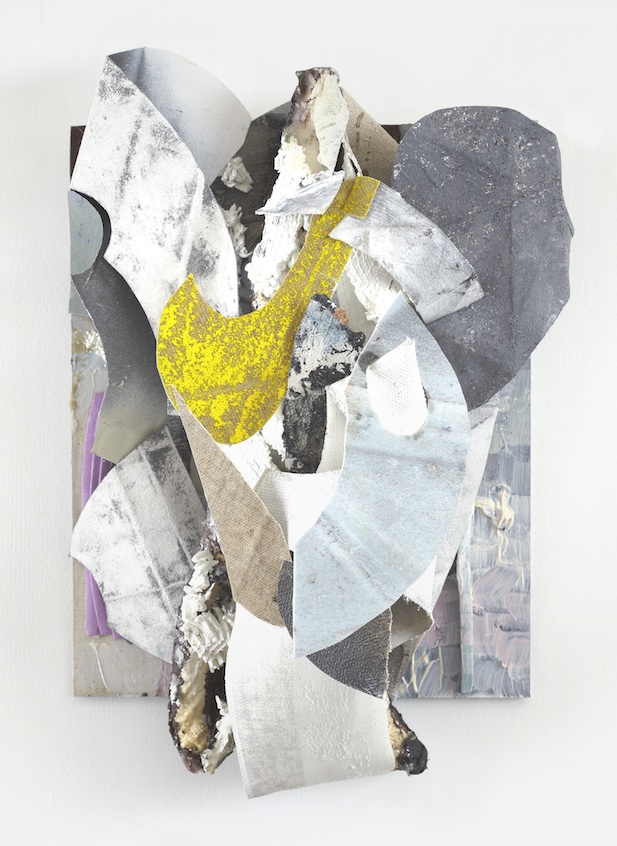

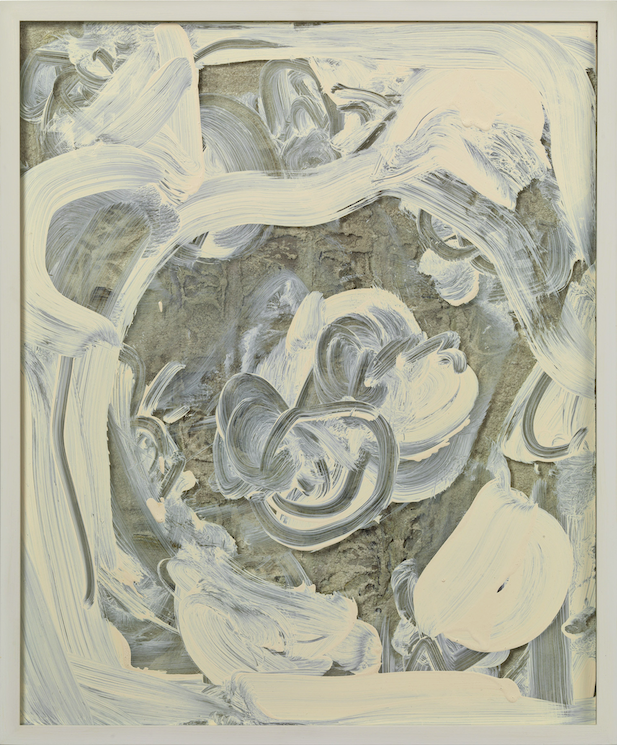

In a day, we experience most images with a cursor, by linking to them or navigating away. There’s something about painting that will always resist that, and a lot of artists today embrace this resistance to an extreme. They go where the materials take them, not where the history of painting tells them to go. In our show we’ve brought together works that are stained, rubbed, torn, collaged, sprayed, frayed, printed, stitched, glued, smeared, stretched, and so on. Some works are years in the making; others are assembled more quickly or painted in a day. Regardless of its duration or method of construction, painting can offer a frame for contact.

Of course, for painters, much of this time spent thinking and making happens in what we all call a studio. I don’t think it’s very useful to romanticize the notion of the studio as a sacred or mysterious space, because the studio can also be a very real space of thinking that extends beyond its walls. The studio is a function of production, not just a site of it. The painters I find most interesting today are always in the process of resisting that which threatens to become typical or routine in the work.

Courtesy of the artist and CANADA, New York

CT Painters are also resisting the traditional boundaries of the medium more and more, as theorists like David Joselit have begun to make clear. The press release of your show stresses that “painting increasingly crosses paths with sculpture, poetry, film, design, fashion, publishing, music, and performance, as well as disparate histories of art, craft, and visual culture.” How do you think the exhibited artists embody this tendency towards a hybrid approach to painting?

BARTHOLOMEW RYAN A lot of our thinking in relation to this tendency is gleaned from spending time with the artists in their studios, talking about their ideas, and understanding the range of things that attract their attention. While we are talking about very different individuals, each of them work in what might nominally be called abstraction, but it’s not abstraction writ large. Art historically, abstraction has become such a concrete precedent in terms of its visuality that its use now becomes representational through the way it conjures past styles. Nevertheless, where representational aspects occur, it’s not so much citation as referencing and moving on. Also, abstract painting can and does allude to a lot of other visual cultures, styles, and contexts. I think the artists are aware of this and prefer that their work hover in some area where it can’t quite be located but invites the viewers to make their own associations.

This line of questioning feeds into another that prompted the exhibition, one that often comes up, where an older generation of critics, curators and artists encounter a younger painter’s work and ask, “Where is the criticality?” In the critically aligned art world of the last 30-40 years, there has been this expectation that for a painter to continue as a painter there has to be some basic level of self-reflexivity, some wry acknowledgment of the problematic status of continuing to paint in the postmodern era where painting itself had been toppled from its lofty perch. Although this is an important approach to painting, I think there are both young and old painters out there who don’t see painting as this hugely burdensome medium that they somehow need to account for.

Courtesy of the artist and Laurel Gitlen, New York

CT Historically, this kind of criticality has also engaged with traditional modes of presentation, a problem that has been the subject of myriad experiments by both artists and curators. How are you dealing with the question of installation and display within the exhibition?

EC All of the artists in our show have agreed to create new work specifically for it, so there is still a great deal to sort out in terms of the installation before our opening on February 2. The Walker galleries are very much in keeping with the traditional white cube, and they often host more interdisciplinary or installation-based projects. So, in contrast, “Painter Painter” may seem a bit traditional for us. And I think that’s a good thing. Painting offers a closed frame, and the gallery does too, so we keep pushing back at it to open that frame up.

The trick is to balance what’s known with what might reveal itself in the process. We’ve invited Matt Connors, for example, to respond to our installation with a sculptural intervention, and Molly Zuckerman-Hartung is at work on a sprawling floor-bound piece that takes painting off the wall. Jay Heikes will install an arrangement of tool-like objects hung on the wall— this is work that has evolved directly from our ongoing conversations with him about the history of the history of the avant-garde, his reading of artist manifestos, and the overdetermined nature of painting as a medium. Questions of display and the space of the exhibition have been somewhat secondary to our studio conversations, but this has been uniquely generative because we’ve come to know the highly relational ways in which these artists are thinking and working. How do you surface the complexities of a relational practice within the rigid framework of a museum group show? That feels like the real crux of curating painting today, and there’s no easy answer.

Courtesy of Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London and Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

CT Can you mention any group exhibitions, particularly of painting, both recent and historical, that you’ve drawn inspiration from for the show?

BR Working at the Walker, we were influenced in part by our own history. The last time there was a group-painting exhibition here was the Douglas Fogle-curated “Painting at the Edge of the World” in 2001. As the title implies, it presented itself as having a global reach, and traced historical and contemporary practices that expanded the scope of painting, often away from the wall into other more distributed postmedium practices. In a way it was an attempt to create some space around the medium by foregrounding its malleability: painting as attitude at the dawn of the new Millennium. Jeffrey Deitch’s “The Painting Factory” at MOCA this year claimed to be the first major review of contemporary abstract painting, and, predictably given the source, positioned this phenomenon as leading from the breakthroughs of Andy Warhol. So there was an emphasis on seriality, industrial processes and the readymade gesture. MCA Chicago’s “Phantom Limb” (also 2012), while not exclusively related to abstraction looked to Rauschenberg and Warhol as the canonical figures who paved the way for generations of artists who continue to critically engage “the romance of the artists hand.” While many of the artists included in these two exhibitions are very important, the frames don’t seem relevant in relation to our exhibition, which is decidedly not about challenging, yet again, the romance of the artists hand, or about following that deadening feedback loop that leads through Modernism to its aftermath.

There were definitely a number of recent smaller-scale exhibitions that interested us: The Kitchen’s “Besides, With, Against, and Yet: Abstraction and the Ready-Made Gesture” (2009), which almost didn’t need a press release because the title says it all, and the “Gambaroff, Krebber, Quaytman, Rayne” exhibition at Bergen Kunsthalle (2010). But, I would say most of our inspiration came from listening to the artists and visiting their studios, as well as various texts we encountered in our research that seemed to sidestep some of the above.

CT The exhibition gathers American and European artists. Do you envision any particular outcome from this juxtaposition in terms of the different art-historical traditions they’re indebted to?

EC After repeated studio visits during our research, we have ended up with a group of painters from America and Europe, although the show isn’t so much about difference at that level. I will say, though, that the European artists we visited have really internalized aspects of European informalism in ways that their American peers have not; and that Minimalism, twentieth-century design, and early modernism come up a lot in our conversations with American painters. But those are very rough generalizations. Ultimately the Internet is the great leveler. The idea of being indebted to an art-historical tradition is no longer rooted in place. Painting’s terms are now totally searchable.

Courtesy of the artist; Shane Campbell Gallery, Chicago; Lisa Cooley, New York; and Laura Bartlett Gallery, London; Photography by Brian Forrest

CT Speaking of the Internet, mobile. walkerart.org will host a series of online studio visits with the artists as a complement to the exhibition. Can you tell us more about this content, and how the idea came about? It’s quite an interesting example of how the exhibition format and the curator’s work, as well as the museum’s reach, can transcend the limits of the physical space.

EC The content is just starting to appear online. We’ve posted an interview with Alex Olson about her painting practice and a text by Sarah Crowner on her recent artist’s book published by Primary Information. A lot more to come: Joseph Montgomery will be writing about his forthcoming solo exhibition at MassMOCA, and Rosy Keyser has begun documenting her work and life upstate in Medusa, NY over the winter months. Zak Prekop just finished a piece on the Chicagobased musician Kevin Drumm, and Charles Mayton is sending us texts and images from Paris where he just installed an exhibition at Balice Hertling.

BC We invited the artists to respond to an invitation to produce an online studio visit, and that could mean whatever seemed relevant for them. While we’ve paid a lot of attention to the studio as a material site of production, we’re also attentive to the studio as a dematerialized condition, as a way of looking at and being receptive to the world. The nature of this invitation, about being part of an ongoing dialogue, is also why it turns out there will be so much new work in the exhibition, which was by no means a premise we started out with. It’s not about our playing the perfect hand as curators, working from a predefined checklist, but about having the exhibition be a continuation of the conversation with the artists, and hopefully being able to impart some of that quality to the people who come to see the show.

CT Are you preparing a catalogue as well?

EC We discussed a catalogue early on, but the form didn’t seem quite right for the conversations we were having in studios and the content we wanted to generate around the show. With our publications online, we get to continue the conversation through the run of the exhibition — the opening of the show is just a proposal, really. Maybe one day you’ll see all of it in print, but right now it’s more interesting for us to keep the dialogue open-ended and let the show take us where it wants to go.